Do messages and ideas really "go viral"?

Thanks to internet services like YouTube and Twitter, the analogy of content spreading like a virus has gone, well, viral. But is that really how stuff spreads?

That's what this project sets out to investigate.

But first, let's talk about viruses. (The kind that make you sick.)

Viruses spread by person-to-person contact. Little Timmy coughs into his hand, then lends his pencil to little Sammy, and before you know it: Mrs. Maybray's entire kindergarten class is home sick the rest of the week.

Now let's use a model to explore how a virus spreads in a population. Models are interactive simulations we can use to explore real-world concepts—like how a virus spreads through a kindergarten class—without actually getting anyone sick.

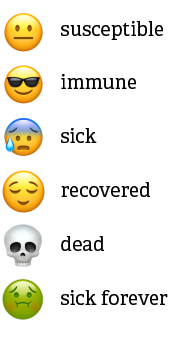

Here's how this model works. There are six types of conditions our population can have:

Susceptible people can get sick if they're exposed to someone who's already sick. This doesn't guarantee they'll get sick, just that there's a chance they will. This model shows how a virus can spread in a population.

Click on any of the squares to make someone sick. Once you run the model once, you can change how it operates by adjusting the settings on the right-hand side.

Math! Emojis! Sickness! Fun!

HELLO mobile reader! This part of this project doesn't work very well on small screens. Click here to try it anyway.

Now that we have a basic understanding of how viruses spread, we're ready to talk about how the viral analogy got applied to the world of messages, ideas, and marketing.

It all started more than sixty years ago.

H.G. Landau and Anatol Raport were the first to compare the spread of information to the spread of diseases, in the 15th edition of the Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics in 1953. They were primarily interested in the abstract mathematical possibilities of the viral model, and didn't apply it to the real-world.

Nearly a decade later, public health scholar Vaun Newill and scentist William Goffman published a paper in the journal Science, in which they argued that models of disease diffusion could be extended to describe other situations, such as the spread of ideas in a culture. They wrote:

People are susceptible to certain ideas and resistant to others. Once an individual is infected with an idea they may in turn, after some period of time, transmit it to others.

Things were relatively quiet in the messages-are-viruses world after that.

The internet renewed interest in this idea.

Many popular books were written about viral marketing and viral media in the 1990s and early 2000s.

In the Media Virus (1994), author Douglas Rushkoff insisted that "this term is not being used as a metaphor. These media events are not like viruses. They are viruses. They spread rapidly if they provoke our interest, and their success is dependent on the particular strengths and weaknesses of the host organism, popular culture. The virus code mixes and competes for control with the cell’s own genes, and, if victorious, it permanently alters the way the cell functions and reproduces." |

In his 2007 book The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell said the "best way to understand the emergence of fashion trends, the ebb and flow of crime waves, or the rise of teenage smoking, or any number of the other mysterious changes that mark everyday life is to think of them as epidemics."Ideas and products and messages and behaviors spread just like viruses do." |

And in Unleashing the Ideavirus (2000), Seth Godin breaks down the analogy even further, saying that sneezers "infect the masses" with contagious ideas that spread far and wide, passing from person-to-person. |

And those are just the big names of viral marketing.

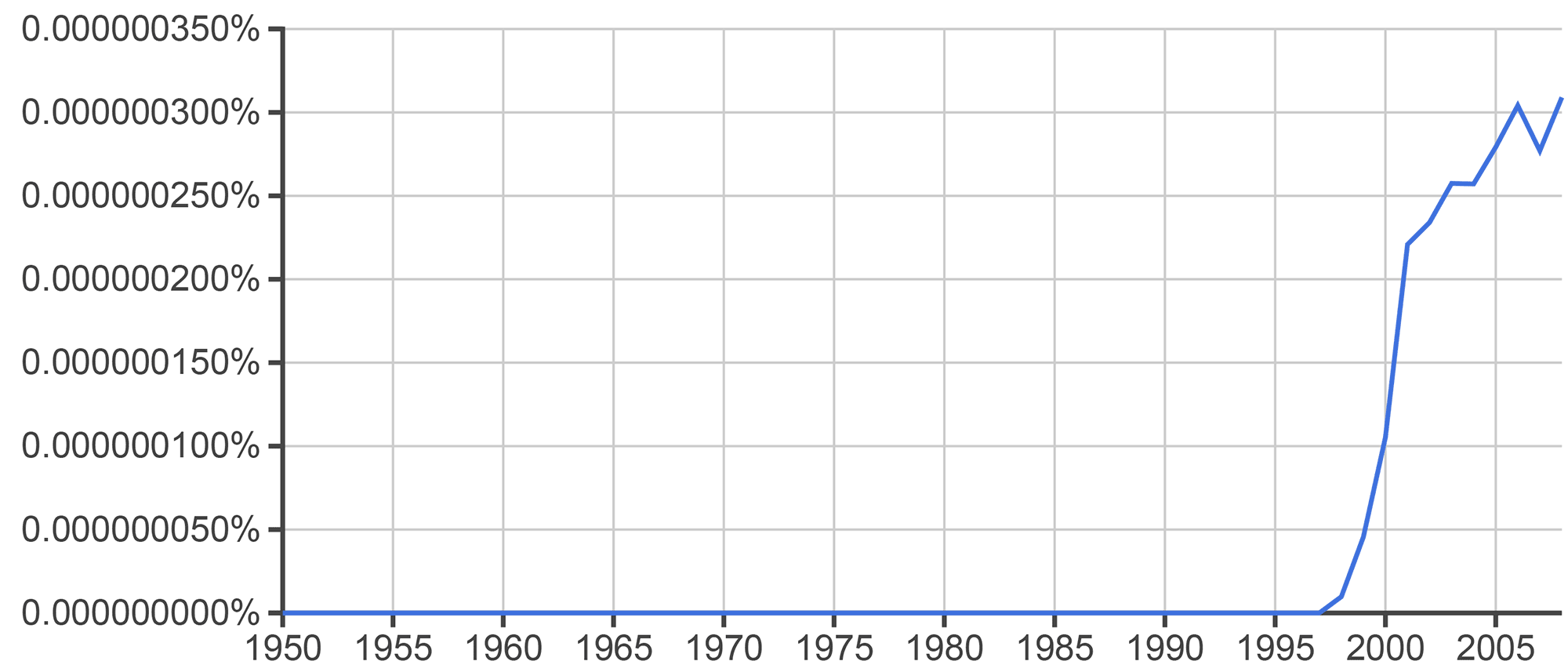

Check out how many books contained the phrase viral marketing by 2008. Sure, the count reaches just over 0.000000300%. But that's the percentage of all the books published in English during that period. And look at that growth rate!

Let's explore this idea with an example.

The typical story told by the proponents of the viral analogy goes something like this.

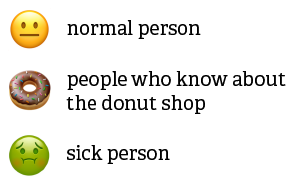

Remarkable products spread from word-of-mouth You tell a friend about a cool new donut shop, they tell their friends, who then tell their friends.

Pretty soon the shop has a line wrapping around the block every morning. The idea (that donut shop is good) spreads from person-to-person, just like the chicken pox virus spreads from person-to-person, until it infects an entire kindergarten class.

Now let's explore this example with a model. This model has three conditions. Here's the key:

Now let's play with the model.

HELLO mobile reader! This part of this project doesn't work very well on small screens. Click here to try it anyway.

There's just one tiny problem with the scenario on which the above model relies.

Messages and ideas don't really spread like viruses.

When people claim that ideas spread like viruses, they’re using what sounds like an empirical scientific theory to validate their belief that word-of-mouth communication is the future of marketing in the digital age.

But in reality, their work borrows the prestige of a biological process to give credibility and a cohesive narrative to a selection of handpicked anecdotes and case studies that happen to validate their proposition.

But if ideas don't go viral, how do they spread?

This project introduces a new way to understand the spread of ideas in a culture. It uses the analogy of an ecosystem, in which a state of semi-equilibrium is maintained, as individuals are influenced by a complex chain of motivations including the need to signal group affiliation. The ecosystem analogy better describes the spread of messages and ideas in the realms of fashion, linguistics, and other real-world phenomena, as we will see.

The idea for this new analogy emerged from conversations I had with people from the worlds of linguistics, fashion design, health and wellness, entrepreneurship, academia, political science, graphic design, and more.

Hear me out. Check out the interactive stories below.